“Les Sorcières-Théoriciennes,”

an encounter between theory and domestic space.

Documentary work produced as part of the “L.i.p Collective” workshop, initiated by Le Signe - Centre National du Graphisme, common-interest collective (Corine Gisel and Nina Paim) and Madeleine Morley April-May 2020.

Tidy up and disturb is the loop of actions so well known by housewives. By exhausting themselves, even if they are blind to the task, it is no longer a question of thinking, reflecting or even theorizing: “She who does not theorize squints her weak and myopic eyes, made for the crumb and the anecdote.”

In 1978, Marianne Alphant wrote a short text for the French literary and feminist periodical Sorcières, whose bimonthly and then quarterly publications nourished a nascent network of women artists, theorists, writers and even housewives. This text, entitled “Ranger/Déranger”, closes a corpus of texts dedicated to women and theory, whose editorial reveals the disagreements and debates that marked its publication: halfway through the 24 issues of Sorcières, “Théorie” breaks an editorial balance that had hitherto been “differentialist”, i.e. defending a difference between the sexes that should be valued as such, particularly in the field of arts and literature. “Feminine writing” would be the result of a biological and social condition, and would allow the emergence of new forms of writing, far from the masculine carcass of “speaking straight, with square words, with straight sentences, in orthodoxy.”

However, while the ten texts that precede it revolve around a “making theory” that has already been defined (by men, long ago, we no longer know), “Ranger/Déranger” moves the theory into a space that is unknown to it: the domestic space. To tidy and disturb are gestures produced by housewives as much as by theorists: “a theory is no other thing: first of all a tampering, a different arrangement, a ‘ranger’[tidy], an inventive practice in the inhabited space: mathematics or the house, the drawer, philosophy, words or threads.” Marianne Alphant turns domestic space into a theoretical breeding ground, theory into a set of trivial gestures and practices.

When the domestic space meets theoretical practice, an expanse opens up to nurture new ways of doing, speaking, writing and thinking. In 1978, this text does not mark its time, yet it embroiders a fabric of knowledge and questions that still resonate today: how do we theorize the anecdotal, the domestic, vernacular life and women's gestures? How has theory been concealed between cake dishes and the iron in feminine intellectual spaces? How does one get rid of the household to start writing? How does one publish in feminist magazines between dishwashing rounds?

Many questions emerge from this reading but above all, it is an immense interest in the side-effects, the context, the conditions of existence of this text, how it lives in its time, what it derives from and what results from it, that have guided this research and documentation project.

[The timeline below classify the harvested contents by categories extracted from the reading of “Ranger/Déranger” and offers a personal vision of the encounter between theory and domestic space].

♥ The following contents can only be viewed on a computer ♥

Living the

domestic space ⤵

Theory from

domestic space ⤵

Theory about

domestic space ⤵

From cleaning

to writing ⤵

Art as domestic

crafts ⤵

1840

Catherine Beecher, Treatise on Domestic Economy.

1924

Dorothy Canfield, The home-maker, New York: Harcourt Brace.

E. Weiss, “Machines à laver la vaisselle” [dishwashers], La Nature, n°2608, March 29, 1924.

1929

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own, Richmond: Hogarth Press.

1930

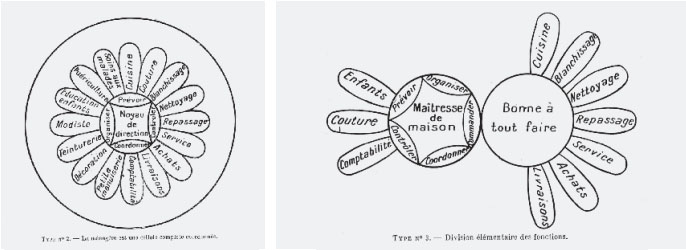

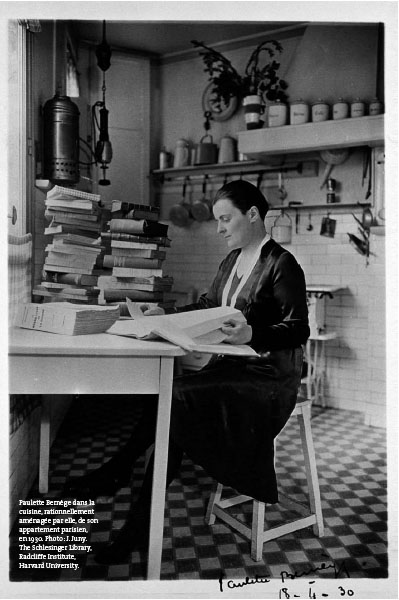

Paulette Bernège was a French journalist, author specialising in home economics. She was a pioneer in the application of scientific principles to the study of domestic science.

✕

[Read more]

Paulette Bernège was a French journalist, author specialising in home economics. She was a pioneer in the application of scientific principles to the study of domestic science.

1933

Paulette Bernège, Quand une femme construit sa cuisine [When a women builds her kitchen], 1933.

1950

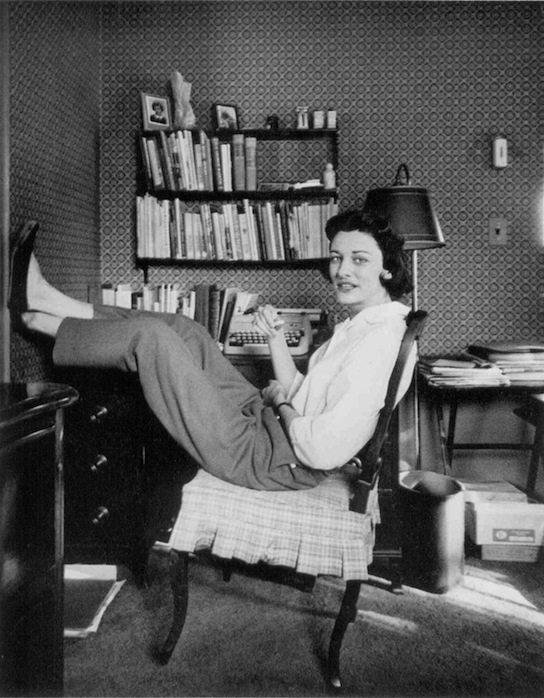

Anne Sexton, Housewife, undated.

✕

[Read more]

Anne Sexton (1928–1974) was an american writer et poet. She opened a path for poetry about feminime topics like abortion, periods, masturbation, adultery, domesticity.

“Some women marry houses. It's another kind of skin; it has a heart, a mouth, a liver and bowel movements. The walls are permanent and pink. See how she sits on her knees all day, faithfully washing herself down. Men enter by force, drawn back like Jonah into their fleshy mothers. A woman is her mother. That's the main thing.”

Anne Sexton, Housewife, undated.

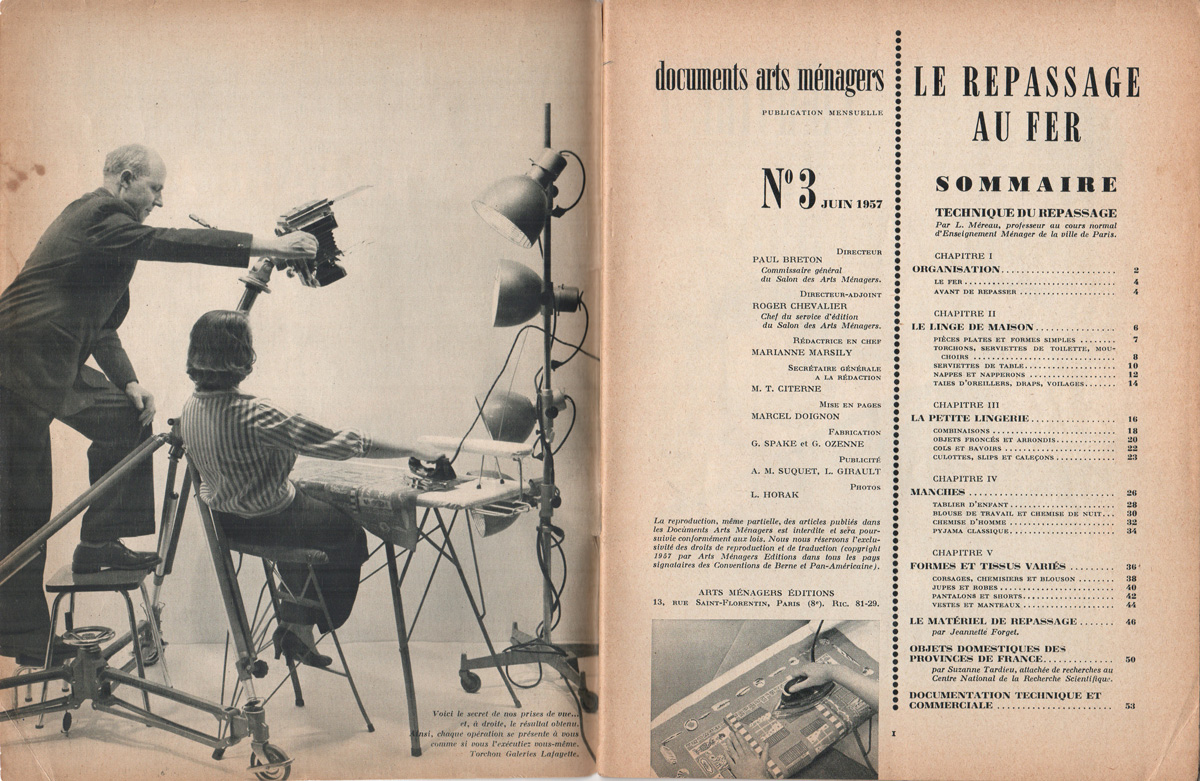

1957

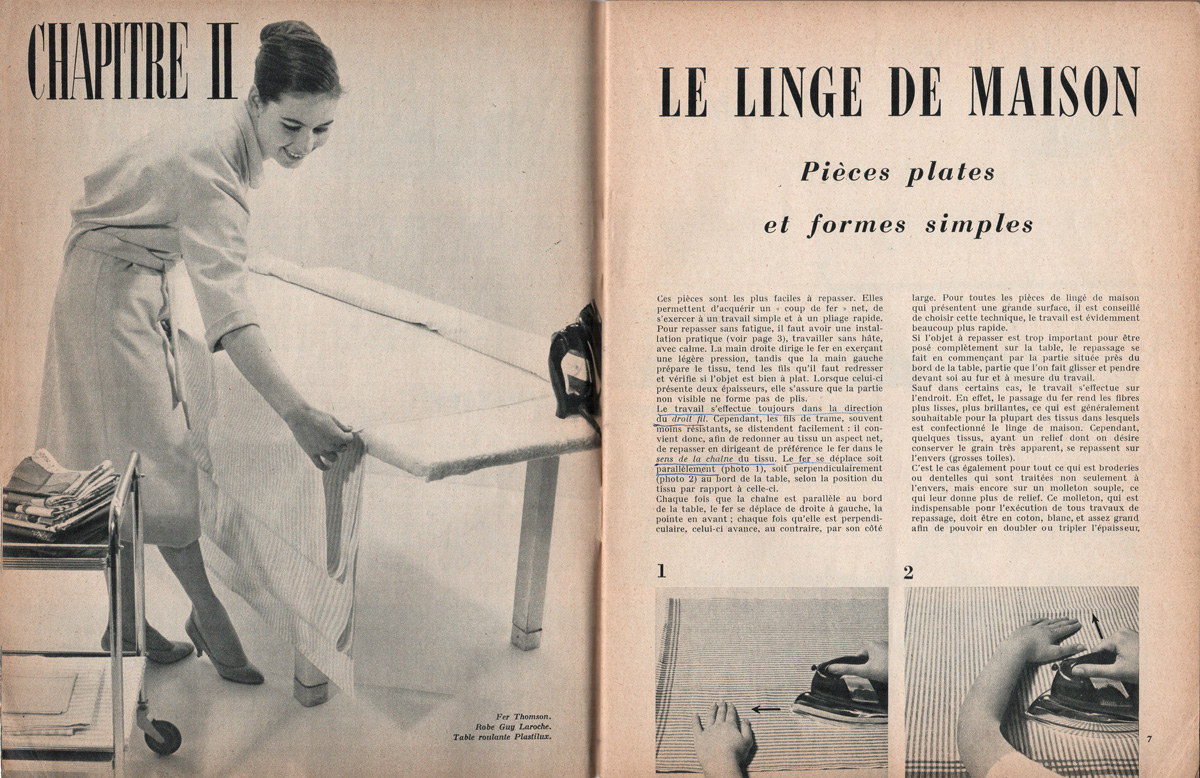

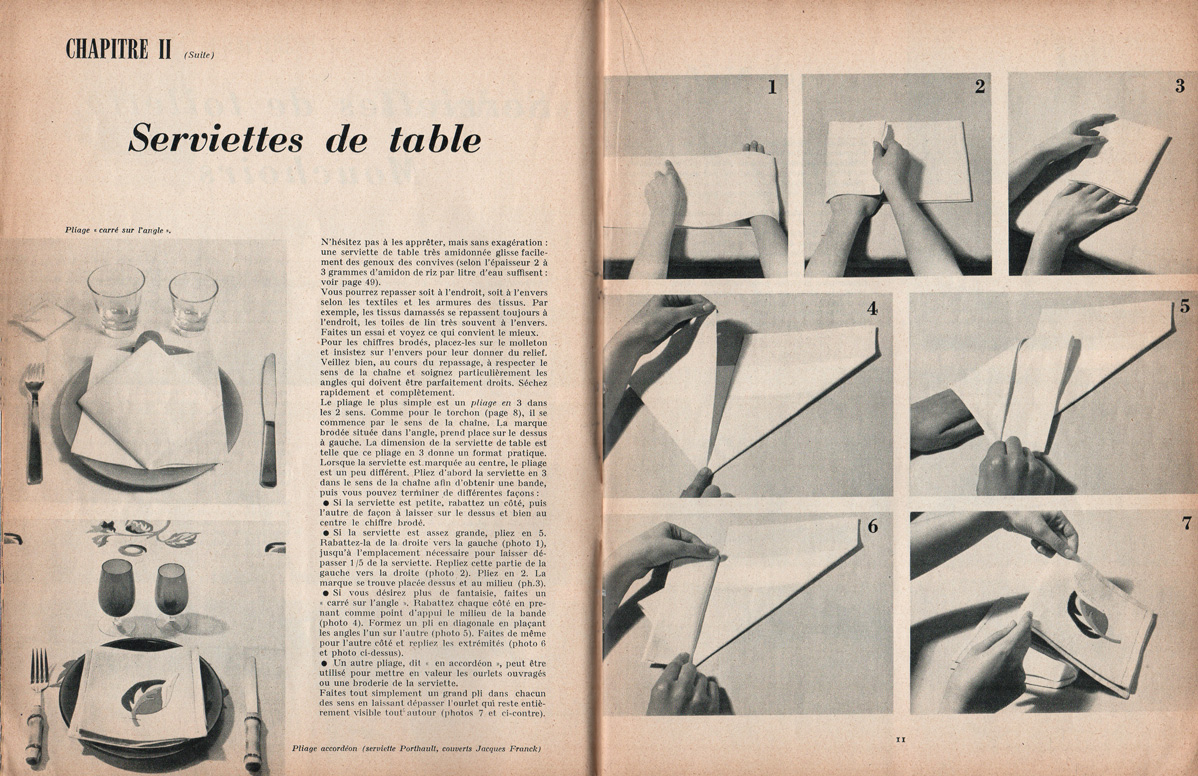

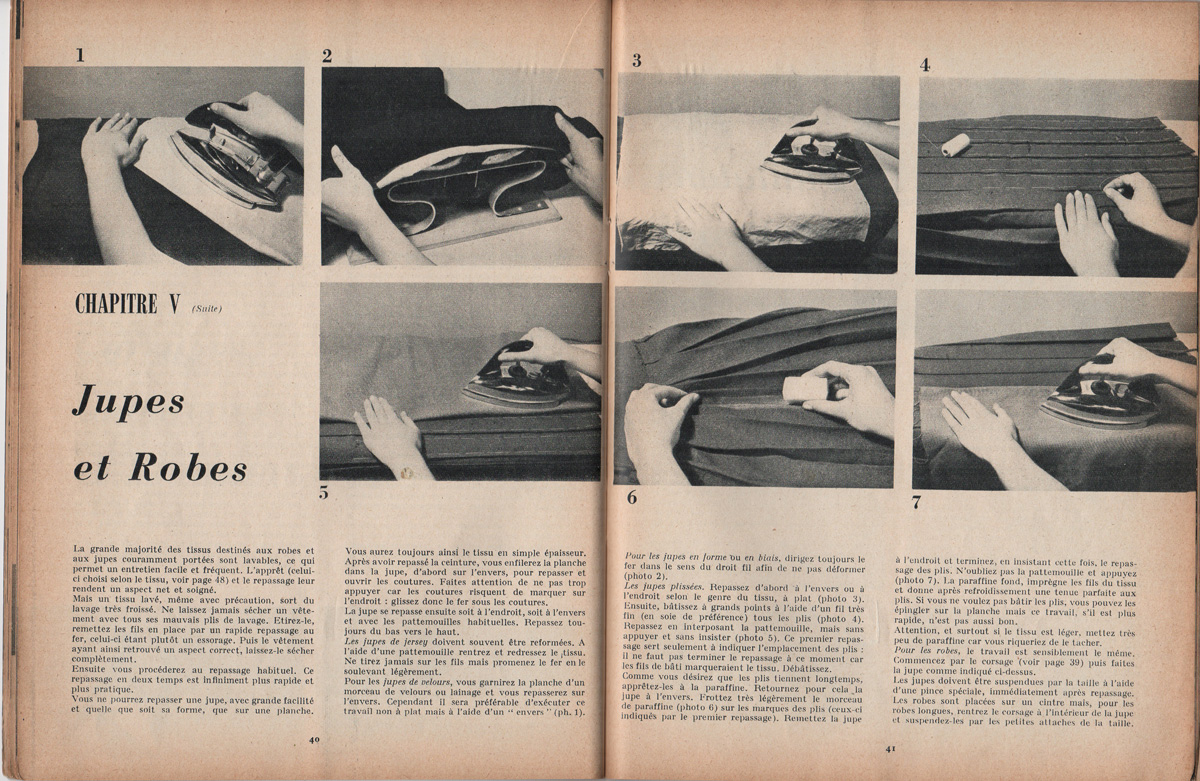

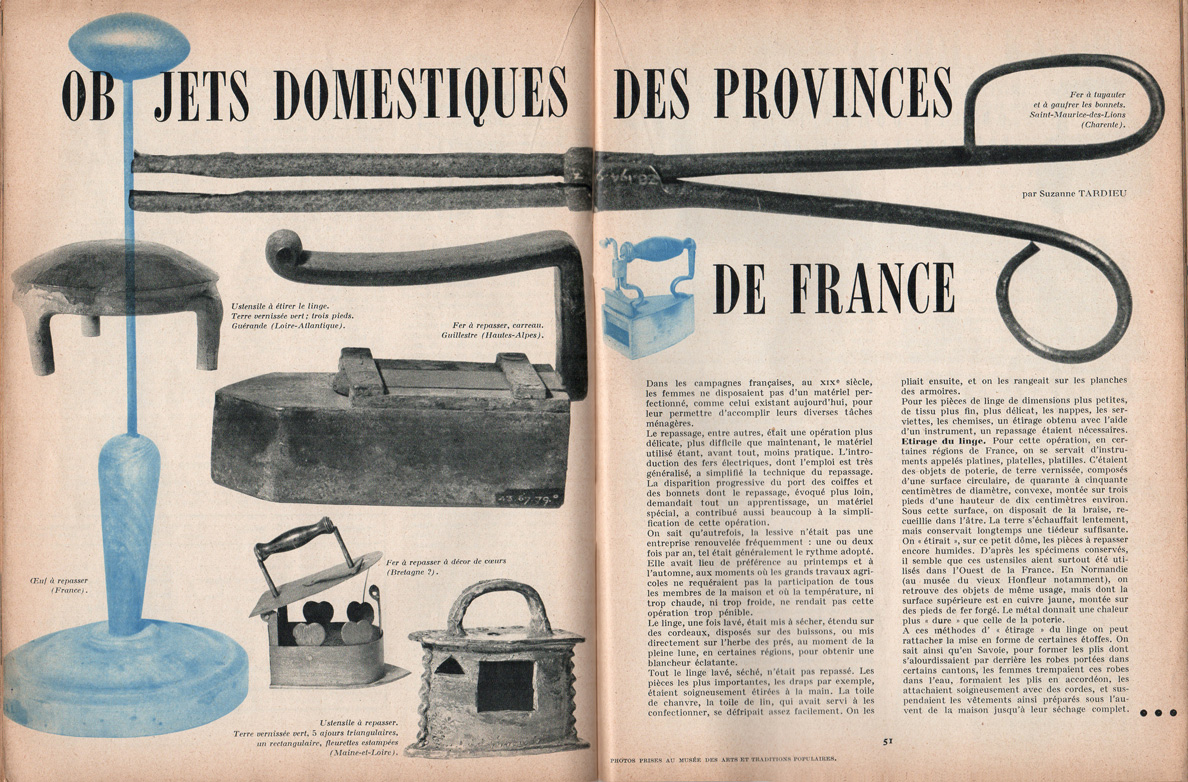

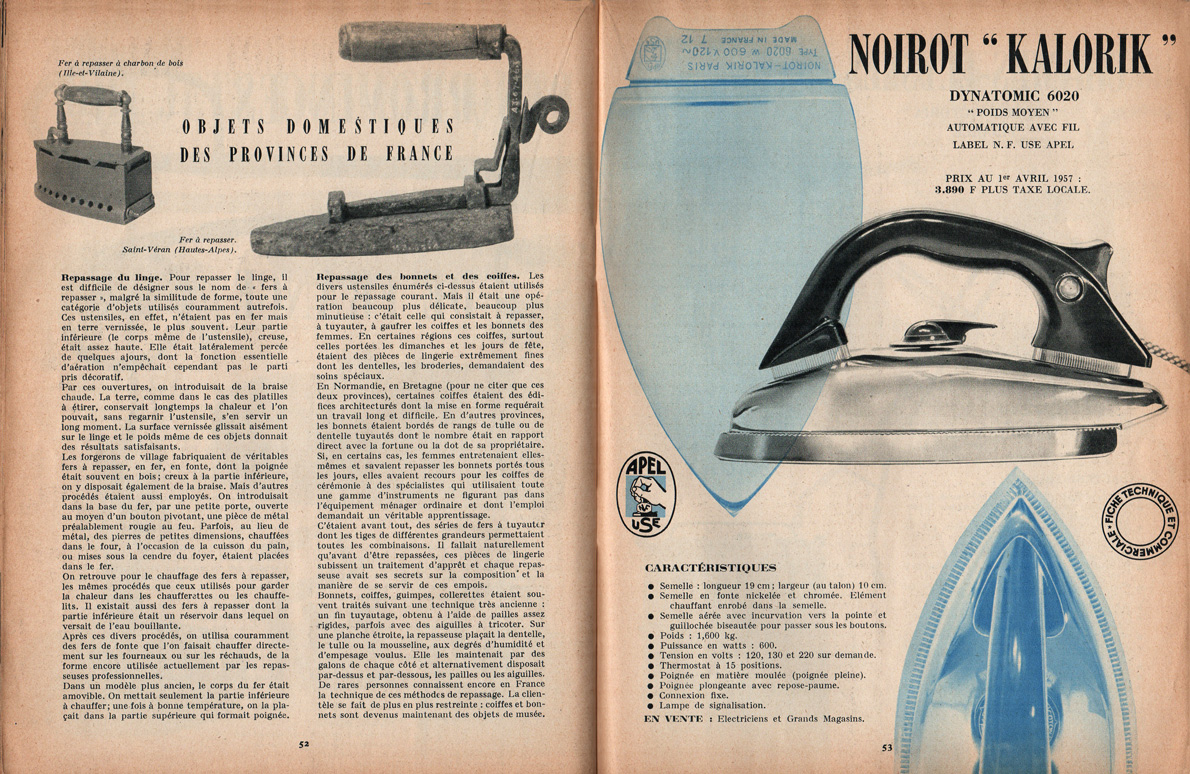

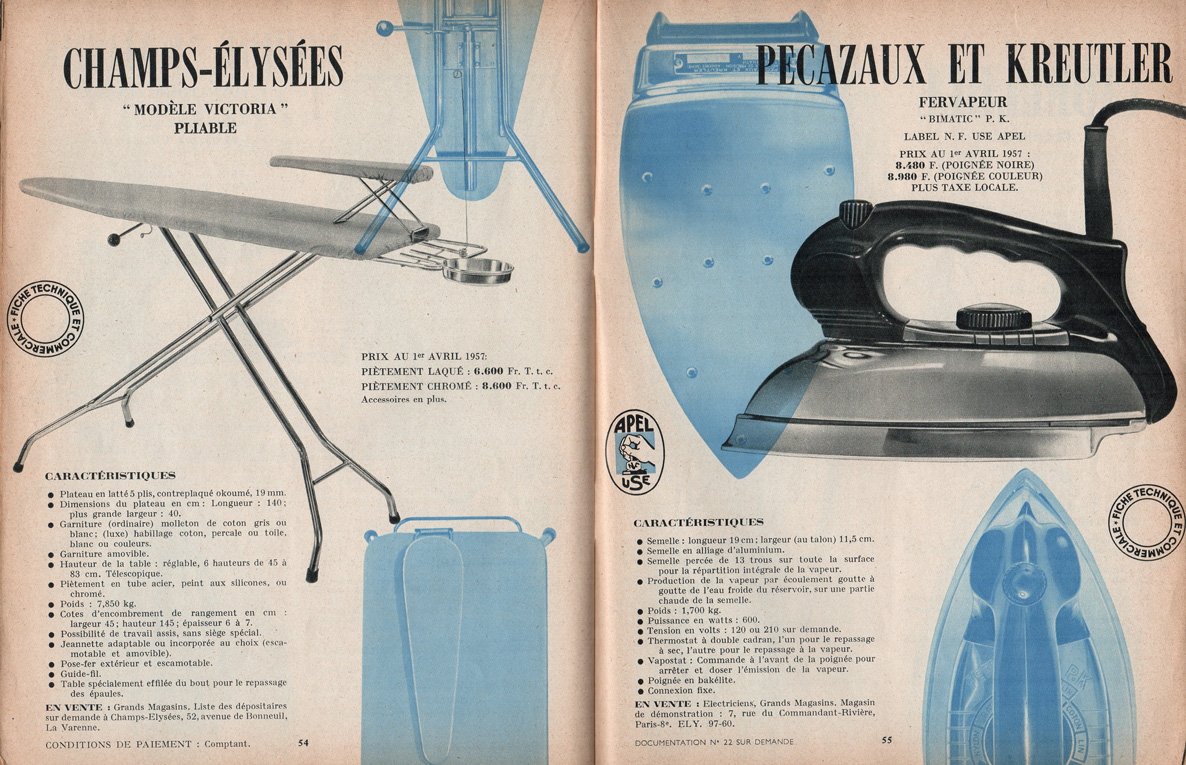

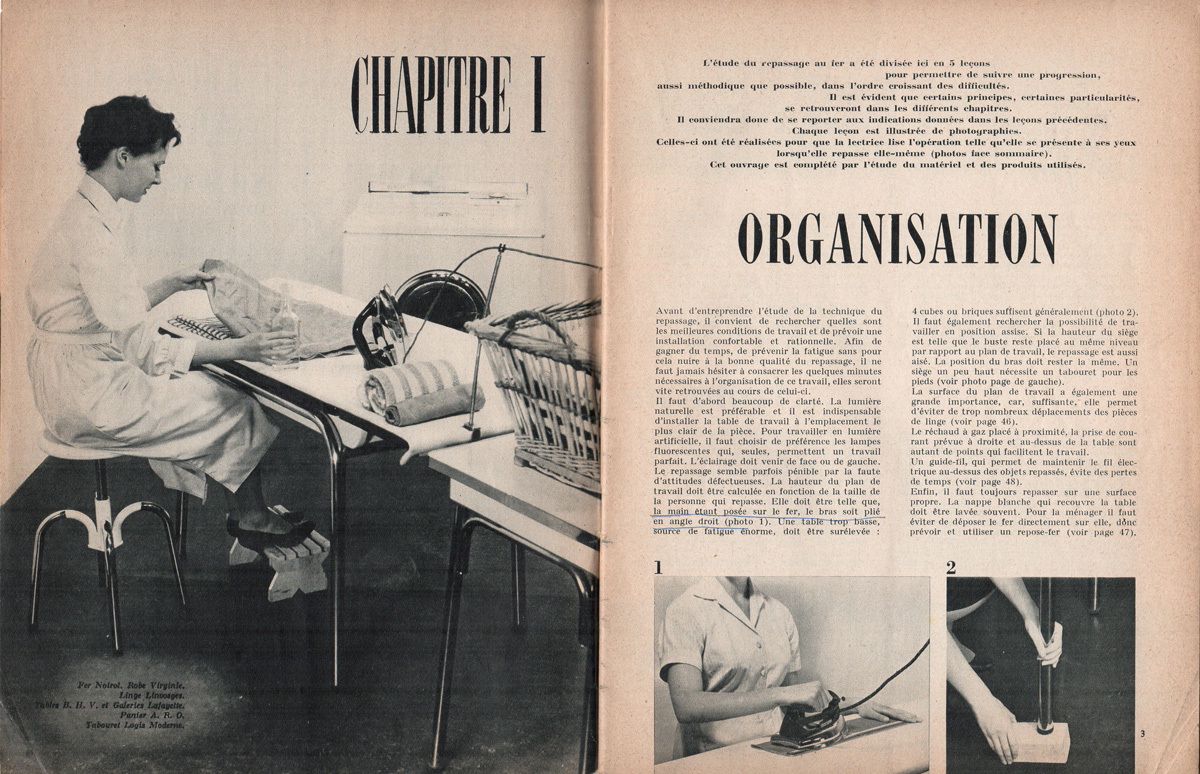

Documents Arts ménagers, n°3, “Le Repassage au fer” [Ironing].

✕

[Read more]

Roland Barthes, “Ornamental Cookery” (“Cuisine ornementale”), in: Mythologies, Paris: Seuil.

1958

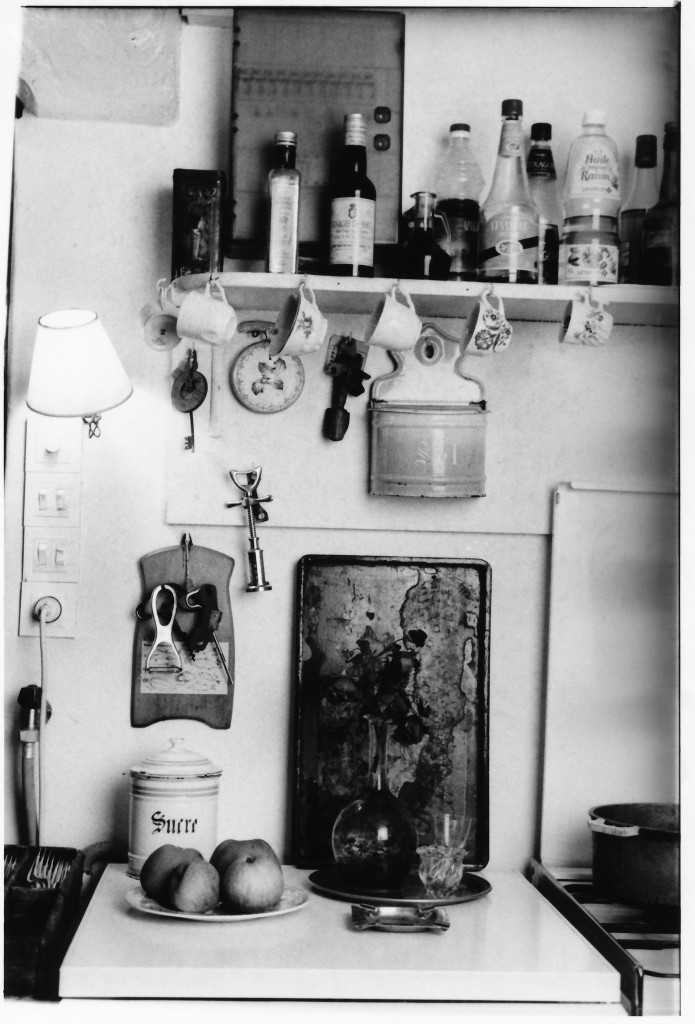

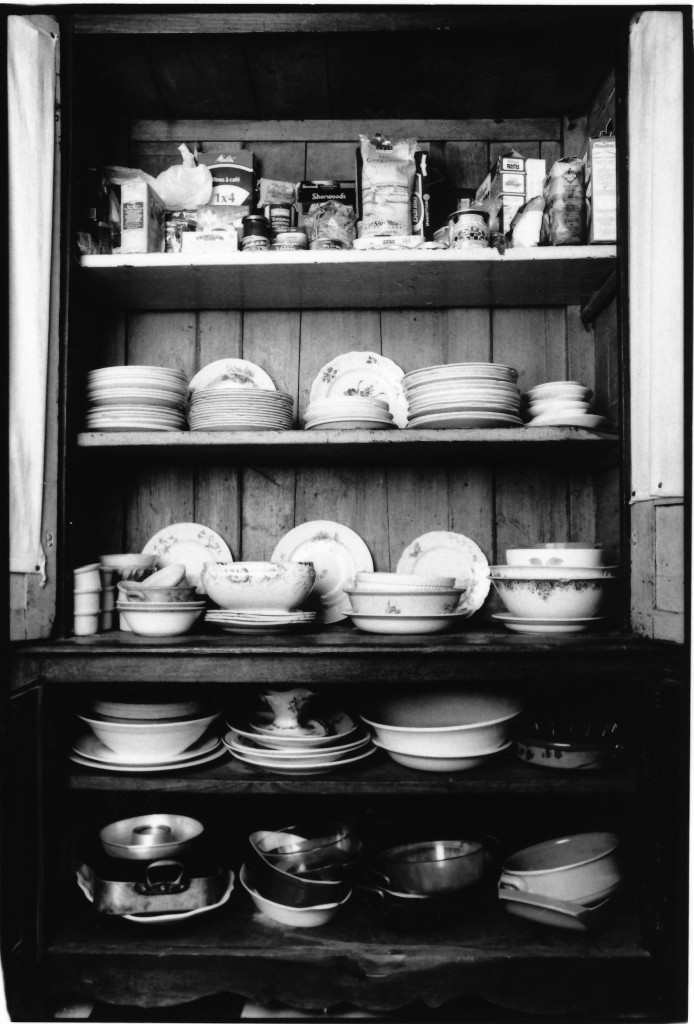

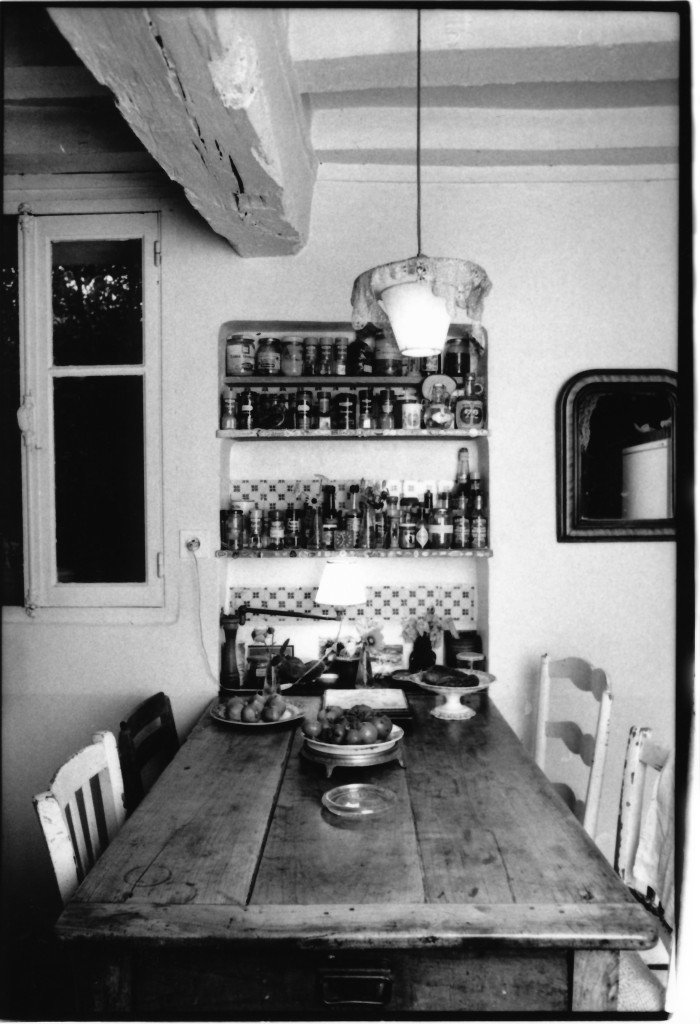

Marguerite Duras bought her house in Neauphle-le-Château in 1958, and her son Jean Mascolo took photos of this place so dear to the writer.

✕

[Read more]

Marguerite Duras bought her house in Neauphle-le-Château in 1958, and her son Jean Mascolo took photos of this place so dear to the writer.

1965

La vie matérielle (@notoriousbigre), tweet on May 26, 2020: “Le bonheur, Agnès Varda (1965)”.

1969

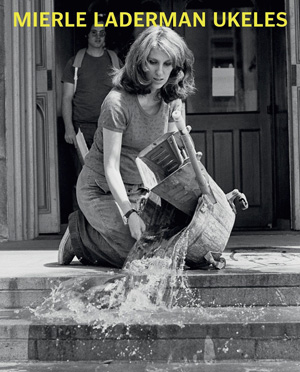

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Manifesto for Art Maintenance.

1971

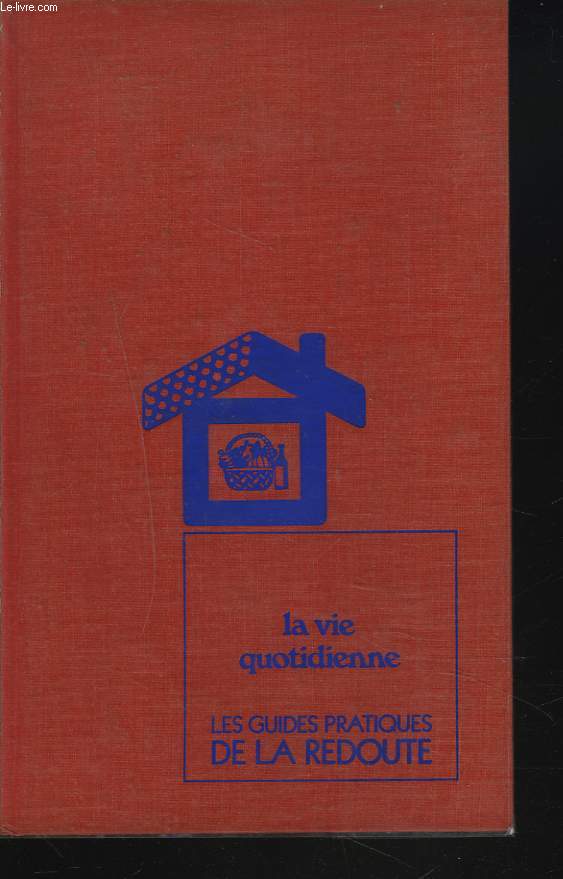

Les guides pratiques de la Redoute, n°1, “La vie quotidienne” (Practical guide about daily life, produced by a famous distance selling french compagny).

✕

[Read more]

Les guides pratiques de la Redoute, n°1, “La vie quotidienne” (Practical guide about daily life, produced by a famous distance selling french compagny).

1972

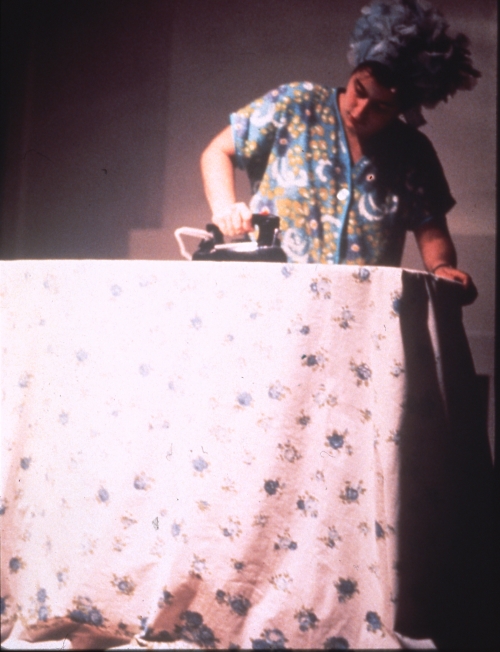

Sandra Ogel, Ironing, from Womanhouse. Performance about the role of women in domestic space : Ironing endless sheets.

✕

[Read more]

Sandra Ogel, “Ironing”, from Womanhouse. Performance about the role of women in domestic space : Ironing endless sheets.

Womanhouse, a large-scale cooperative project executed as part of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts under the direction of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, 1971–72. With a catalog online.

Miriam Chapiro, Expode,(collage).

✕

[Read more]

Miriam Chapiro, Expode, 1972.

1973

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Hartford Wash: Washing, Tracks, Maintenance — Outside and Inside, Wadsworth Atheneum.

✕

[Read more]

“Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939) is a maintenance artist. Since 1969, the year she wrote Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969!, later published in the pages of Artforum, she has devoted her practice to demystifying the invisible labor that undergirds society. ‘Maintenance is a drag,’ she wrote in the manifesto, ‘it takes all the fucking time (lit.) The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom. The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.’ In 1978, Ukeles became the artist-in-residence at the New York City Sanitation Department, a position she continues to hold.”

“ Conversation : Mierle Laderman Ukeles with Maya Harakawa”,The Brooklyn Rail, October 4th, 2016.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Hartford Wash: Washing, Tracks, Maintenance — Outside and Inside, Wadsworth Atheneum.

1974

La grève des femmes [Women's Strike], TV News, June 9, 1972, INA archives.

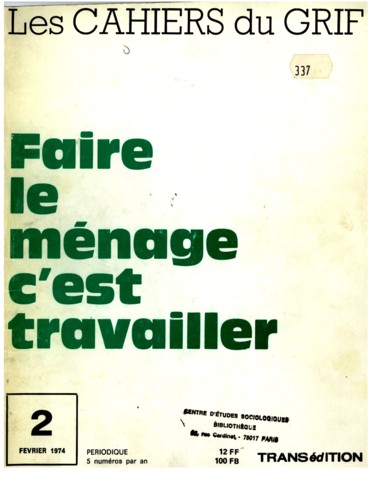

Les cahier du GRIF, “Faire le ménage c'est travailler” [to clean is to work], n°2, February 1974.

✕

[Read more]

Les cahier du GRIF, “Faire le ménage c'est travailler” [to clean is to work], n°2, February 1974.

1975

Chantal Akerman, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

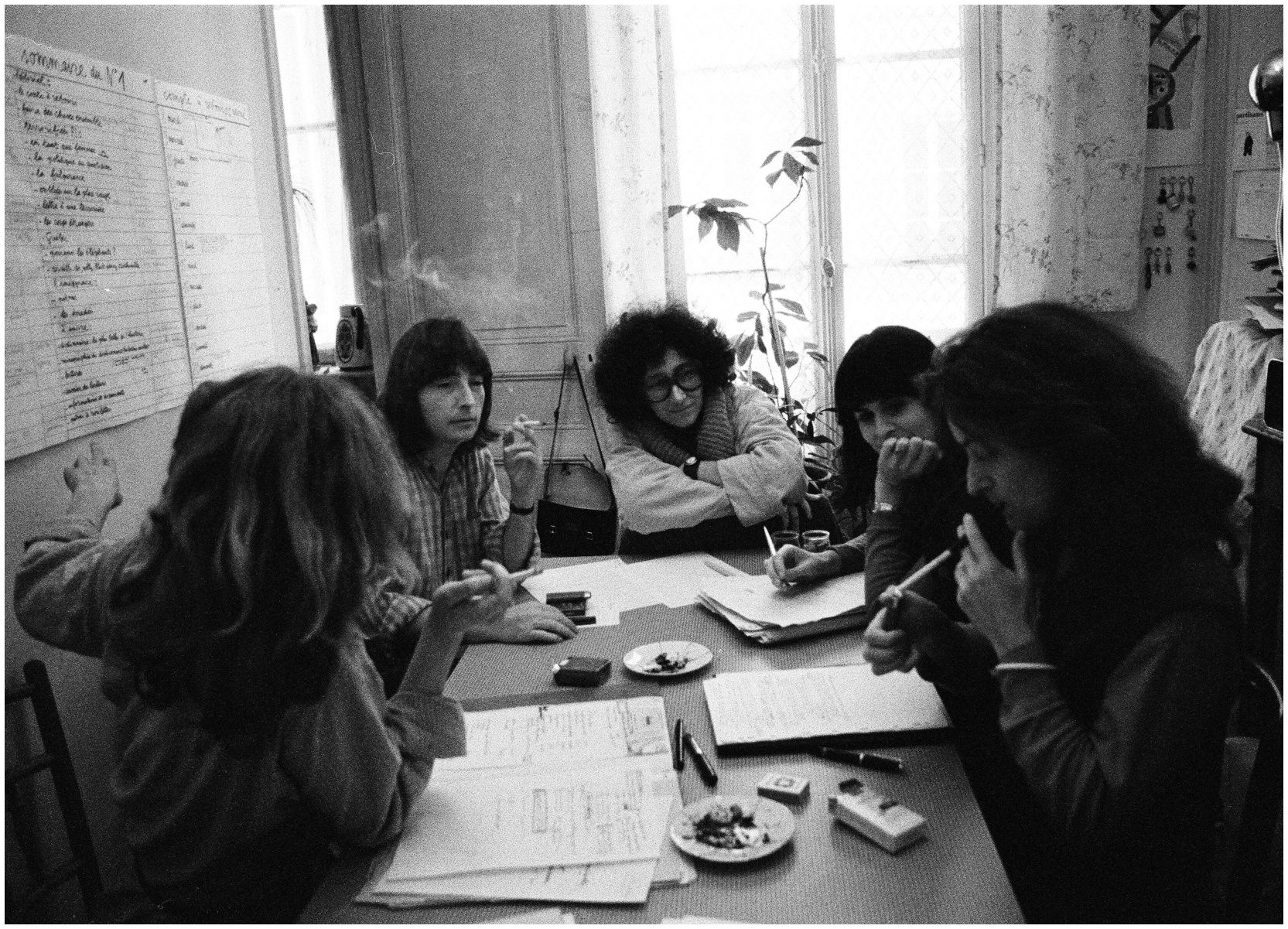

Cathy Bernheim, Feminist meeting at Delphine Seyrig's place: Ioanna Wieder, Claire Delpech, Claire Etcherelli, Delphine Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos.

✕

[Read more]

Cathy Bernheim, Feminist meeting at Delphine Seyrig's place: Ioanna Wieder, Claire Delpech, Claire Etcherelli, Delphine Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos.

Birgit Jürgenssen, “Hausfrauen – Küchenschürze” (Housewives’ Kitchen Apron). The artist describes the imprisoned housewife, who finally melts into the objects she uses every day.

✕

[Read more]

Birgit Jürgenssen, “Hausfrauen – Küchenschürze” (Housewives’ Kitchen Apron). The artist describes the imprisoned housewife, who finally melts into the objects she uses every day.

Hélène Cixous developped the concept of “feminine writing” (écriture féminine) in The Laugh of Medusa [Le rire de la Méduse].

1976

Jacqueline Aubenas, “Abécédaire quotidien et tout en désordre” [Daily Alphabet and Everything Messy], Les cahier du GRIF, n°12.

Jeanne Vercheval, “Les travaux d'aiguille” [Needle Works], Les cahier du GRIF, n°12.

Publication of Sorcières, 1976 – 1982, available online.

1977

French adaptation of “Our Bodies Ourselves” [Notre Corps Nous Même] by The Boston Women's Health Book Collective to the french context.

Claude Boukobza-Hajlblum, “Sorcières… nos traversées” [Witches... Our Journeys], Sorcières, n°7, “Ecritures” [Writings], Paris: Albatros, p. 7-8.

✕

[Read more]

“Quand une femme se met à écrire, ça lui colle à la peau. Pour se séparer de son texte autrement que comme d’un morceau de son corps, il faut qu’elle fasse un détour, qu’elle se demande où ça « s’arrime », cet acte d’écrire ; qu’est-ce qu’elle en fait, de ce système de théories, de connaissances, déjà constitué.”

“When a woman starts writing, it sticks to her. To separate herself from her text other than as a piece of her body, she has to make a detour, she has to ask herself where this act of writing "fits in"; what does she do with it, with this system of theories, of knowledge, already constituted.”

Claude Boukobza-Hajlblum, “Sorcières… nos traversées” [Witches... Our Journeys], Sorcières, n°7, “Ecritures” [Writings], Paris: Albatros, p. 7-8.

Anne Rivière, “Sorcières… nos traversées” [Witches... Our Journeys], Sorcières, n°7, “Ecritures” [Writings], Paris: Albatros, p. 7-8.

✕

[Read more]

“Le jour où il nous sera accordé une 'écriture féminine', elle risque fort de se retrouver du côté de la dentelle et de la tapisserie.”

“The day when we will be granted a 'feminine writing', she is likely to find herself on the side of lace and tapestry.”

Anne Rivière, “Sorcières… nos traversées” [Witches... Our Journeys], Sorcières, n°7, “Ecritures” [Writings], Paris: Albatros, p. 7-8.

1978

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #84.

Maryvonne Daguenet-Teissier, “Le concret c'est de l'abstrait rendu familier par l'usage” [Concrete is the abstract made familiar by use], Sorcière, n°12.

✕

[Read more]

“Le concret c'est de l'abstrait rendu familier par l'usage", Sorcière, n°12, " Un jour peut-être, un(e) étudiant(e) aura un coup de foudre pour une théorie, sans se souvenir du jeu qui l'intriguait enfant. Et si cela n'est pas, du moins ces jeux auront-ils permis d'entretenir une prescience latente, merveilleusement exprimée par les miniatures, décors de palais, parquets et jusque dans les milieux les plus modestes par les filets, broderies, tissages, vanneries, cannages, carrelages, que ce soit en Chine, Egypte, France, Roumanie, Perou ou dans le monde musulman.”

“One day perhaps, a student will fall in love at first sight with a theory, without remembering the game that intrigued him as a child. And if not, at least these games will have made it possible to maintain a latent prescience, wonderfully expressed by miniatures, palace decorations, parquet floors and even in the most modest environments by nets, embroidery, weaving, basketry, wickerwork, tiles, whether in China, Egypt, France, Romania, Peru or in the Muslim world.”

Maryvonne Daguenet-Teissier, “Le concret c'est de l'abstrait rendu familier par l'usage” [Concrete is the abstract made familiar by use], Sorcière, n°12.

Nicole Echard, “Anecdote interdite” [Forbidden anecdote], Sorcière, n°12.

✕

[Read more]

“Dans l'ethnologie (française) tout se passe 'comme' (?) s'il y avait une spécificité du travail féminin, une répartition des thèmes en fonction des sexes, bref un cantonnement partiel de la quasi généralité des femmes chercheurs dans certains domaines ou jardins considérés comme mineurs (femmes, enfants, traditions orales, sous groupes sociaux..), parfois dans certains espaces conceptuels (mais là l'exemple est britannique, la souillure étudiée par Mary Douglas) et dans certaines pratiques (empirisme forcené, art de la description, micro -analyse ...). Cette maniaquerie quasiment ménagère a été productrice de travaux d'une remarquable précision au plan des données, d'une vigilante rigueur quant à l'analyse de celles-ci et d'une incroyable prudence pour ce qui est de leur interprétation, toutes qualités que l'on souhaiterait rencontrer plus fréquemment dans des recherches dont les résultats font loi. Les pratiques étant les garants de l' "objectivité", ces ouvrages féminins et leurs auteurs sont ainsi repliés à l'abri des perspectives théoriques qui s'affrontent avec fracas.”

“In (French) ethnology, everything happens 'as if' (?) if there were a specificity of female work, a distribution of themes according to gender, in short a partial confinement of almost all women researchers in certain fields or gardens considered as minor (women, children, oral traditions, social subgroups...), sometimes in certain conceptual spaces (but here the example is British, the defilement studied by Mary Douglas) and in certain practices (frantic empiricism, the art of description, micro-analysis...). This almost domestic mania has produced work of remarkable precision in terms of data, vigilant rigour in the analysis of the data and incredible caution in the interpretation of the data, all qualities that one would wish to see more frequently in research whose results are the law. Practices being the guarantors of "objectivity", these women's books and their authors are thus sheltered from the theoretical perspectives that clash with each other in such a way as to make the research more objective.”

Nicole Echard, “Anecdote interdite” [Forbidden anecdote], Sorcière, n°12.

Chantal Chawaf, Sorcière, n°12, interview by Françoise T. Clédat.

✕

[Read more]

“Il y a trois langages possibles : la poésie [...], le langage théorique et l'autre langage, le langage de l'impossibilité de travailler l'écriture et d'en faire une oeuvre d'art parce que c'est le cri élémentaire, brut, immédiat qui sort”

“There are three possible languages: poetry [...], theoretical language and the other language, the language of the impossibility of working on the writing and making it a work of art because it is the elementary, raw, immediate cry that comes out.”

Chantal Chawaf, Sorcière, n°12, interview by Françoise T. Clédat.

Marianne Alphant, “Ranger/Déranger” [Tidy/Disturb], Sorcières, n°12.

Heresies, “Women's Traditional Arts – The Politics of Aesthetics”, Vol. 1, n°4.

1979

Dominique Reisenthel, “Aspirateur” [Vacuum], Sorcières, n°19.

Gloria Feman Orenstein, “Paris Salon is Magnet for Artists and Writers”, Women Artists Newsletter, Vol. 5, n°5, November 1st, 1979.

Marguerite Yourcenar was invited by Bernard Pivot in the french Talk Show Apostrophes on December 7, 1979 and January 16, 1981, INA Archives.

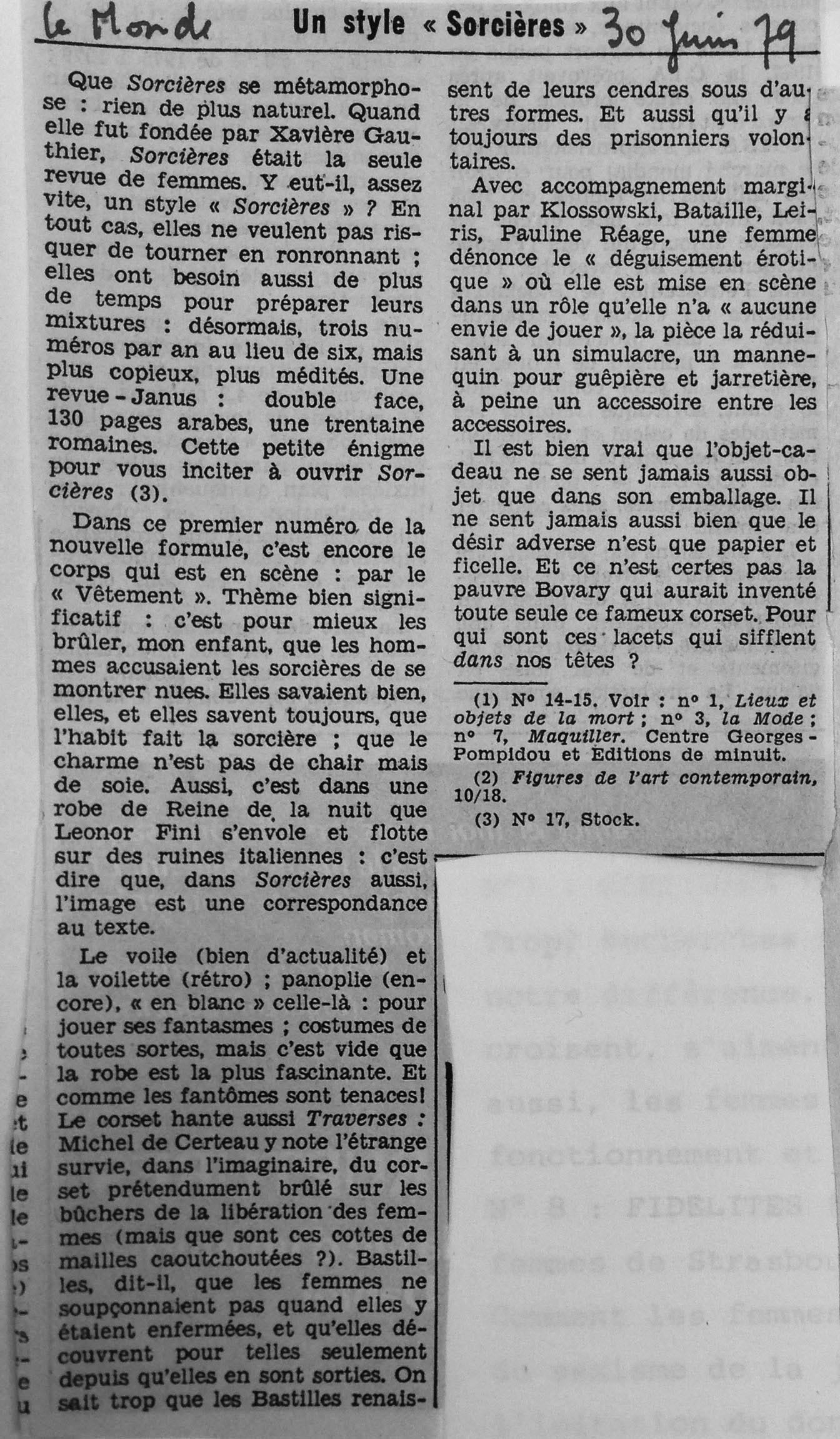

Le Monde, “Un style Sorcières” [A Witches Style], June 1979.

✕

[Read more]

Le Monde, “Un style Sorcières” [A Witches Style], June 1979.

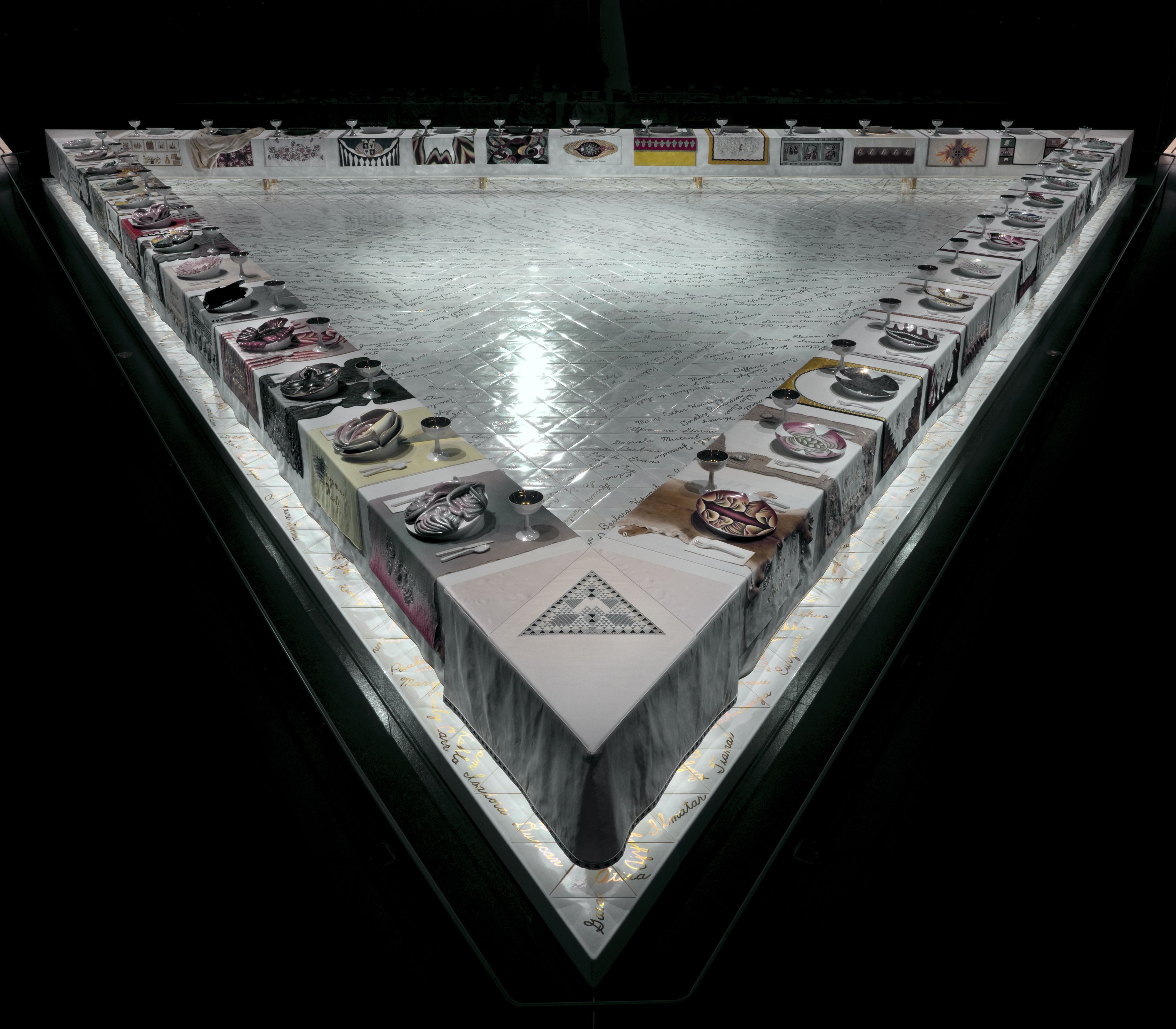

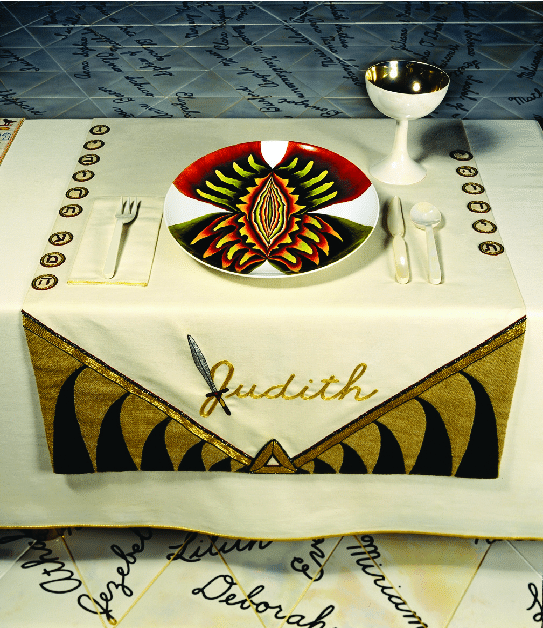

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

✕

[Read more]

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

1980

Creation of the collection of audio books Librairie des voix [Library of Voices], at Editions Des femmes.

Yves Stourdzé, “Autopsie d’une machine à laver”, Culture et Technique, n°3.

When the magazine Sorcières changes publishers for the second time, they find themselves without premises and therefore have to gather at each other's homes.

Cathy Bernheim, preparation of the magazine Parole!, Annette Lévy-Willard, Hélène Rouch, Liliane Kandel, Françoise Picq, Pascaline Cuvelier.

✕

[Read more]

Cathy Bernheim, preparation of the magazine Parole!, Annette Lévy-Willard, Hélène Rouch, Liliane Kandel, Françoise Picq, Pascaline Cuvelier.

1981

Heresies n°11, “Making Room – Women and Architecture”, Vol. 3, n°3.

1982

Antoinette Fouque on the triple working day, intervention at the Estates General against misogyny, national debate, La Sorbonne.

Le Monde, “Des œillets et du yaourt” [Carnations and yogurt], April 5, 1982.

1983

Maïté et la cuisine des mousquetaires [Maïté and the kitchen of the Musketeers], broadcast 1983–1991, INA video archives.

Diane Wood Middlebrook, “Housewife into Poet: The Apprenticeship of Anne Sexton”, The New England Quarterly, Vol. 56, n°4, December 1983, p. 483-503.

1984

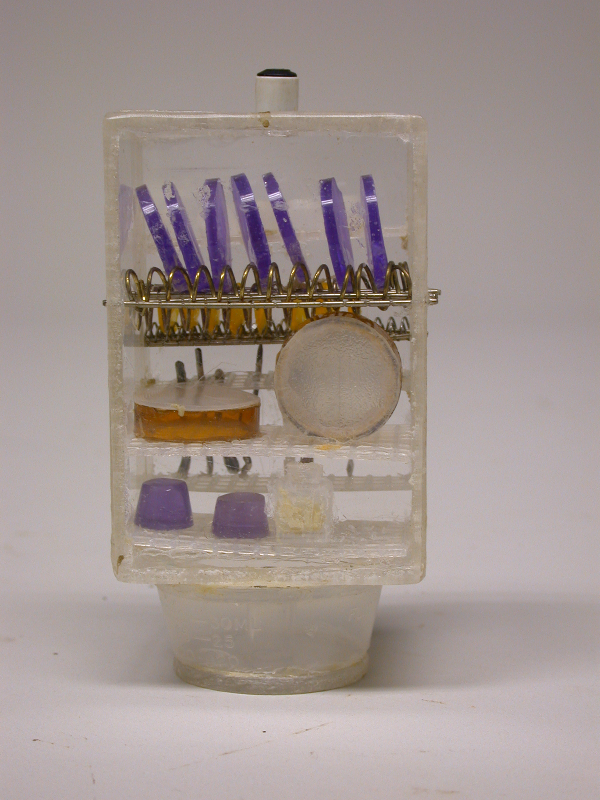

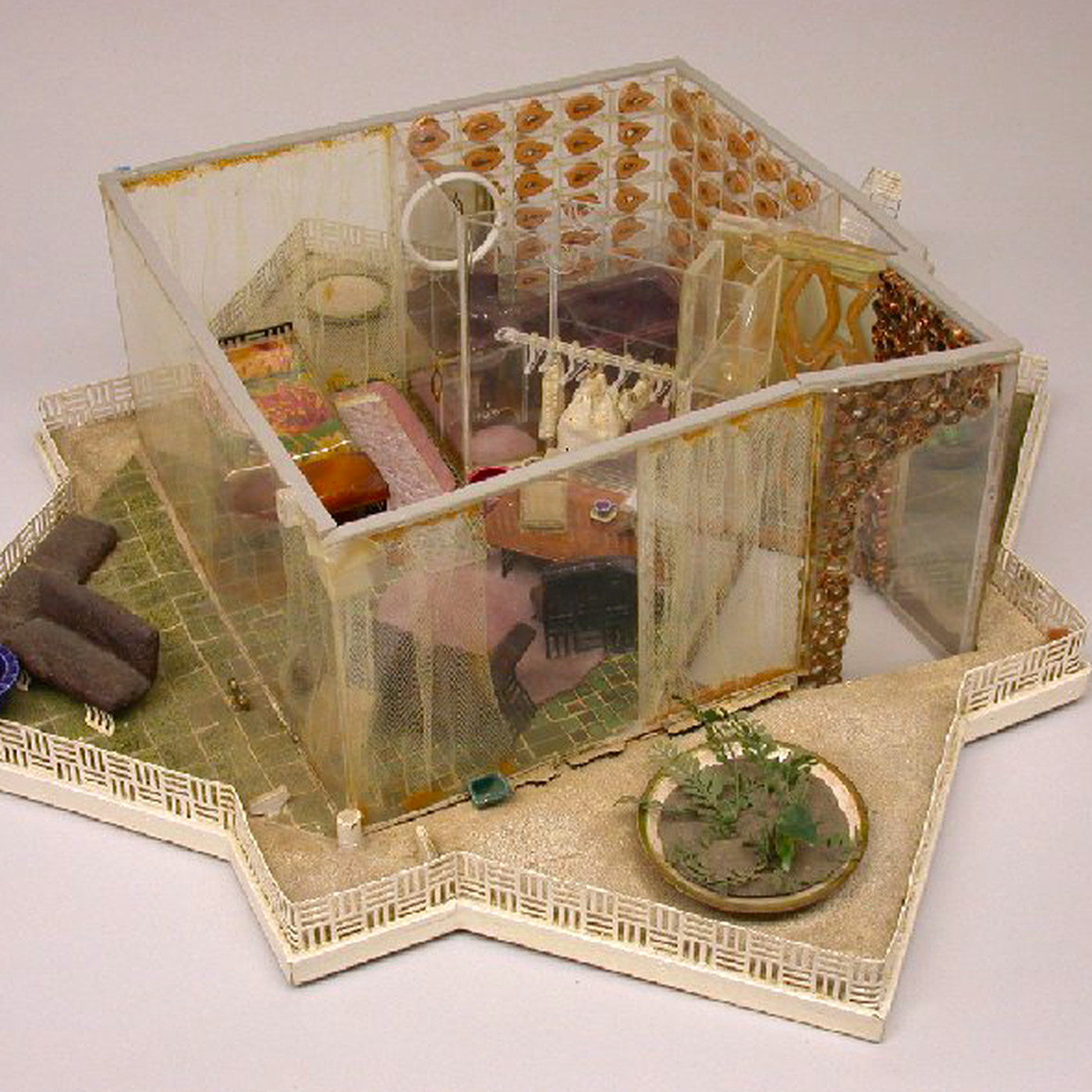

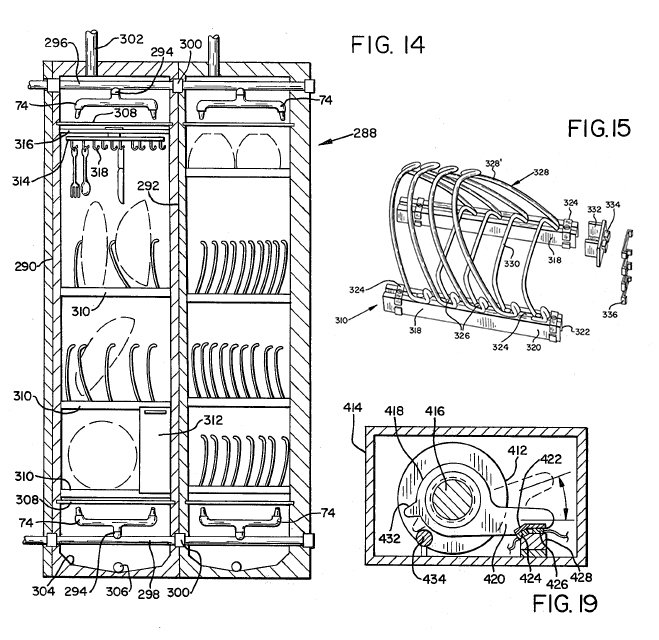

Frances Gabes'self-cleaning house goes on sale for $50,000.

✕

[Read more]

“Frances Gabe, tired of cleaning the jam that her children spread with malicious pleasure on the walls, one day lost her composure, held up the garden hose and hosed down her entire house. She never believed Mr. Muscle's short-term promises. In fact, it was after she threw her husband out of the house that she had, as a divine revelation, the idea of a self-cleaning house.”

Tony Côme, “Habiter le lave-vaisselle. Un rêve de Frances Gabe”, Strabic, April 23, 2019.

Frances Gabe'sself-cleaning house goes on sale for $50,000. She filed a patent, available here.

Frances Gabe about her self cleaning house[Vidéo]

1987

Michelle Perrot, about the trousseau, Traverses, n°40, April 1987.

✕

[Read more]

“Plus qu’à l’écrit interdit, c’est au monde muet et permis des choses que les femmes confient leur mémoire. Non aux prestigieux objets de collection, affaire d’hommes soucieux de conquérir par l’accumulation de tableaux ou de livres la légitimité du goût. Au XIXe siècle, la collection, plus encore la bibliophilie, sont des activités masculines. Les femmes se rabattent sur plus humble matière : le linge ». L’historienne et militante féministe précise : « Le trousseau, soigneusement préparé dans les milieux populaires, ruraux surtout, est "une longue histoire entre mère et fille". La confection du trousseau, c’est un legs de savoir-faire et de secrets, du corps et du cœur, longuement distillés. L’armoire à linge est à la fois coffre-fort et reliquaire. L’épaisseur des draps, la finesse des nappes, le marquage des serviettes, la qualité des torchons prennent sens dans une chaîne de gestes répétés et festonnés.”

“More than the forbidden written word, it is to the mute and permissive world of things that women entrust their memory. No to prestigious collector's items, the business of men anxious to conquer the legitimacy of taste through the accumulation of paintings or books. In the 19th century, collecting, and even more so bibliophily, were male activities. Women fell back on a more humble material: linen". The historian and feminist activist explains: "The trousseau, carefully prepared in working class circles, especially in rural areas, is "a long history between mother and daughter". The making of the trousseau is a legacy of know-how and secrets, of the body and the heart, distilled over a long period of time. The linen cupboard is both a safe and a reliquary. The thickness of the sheets, the fineness of the tablecloths, the marking of the napkins, the quality of the tea towels make sense in a chain of repeated and scalloped gestures.”

Michelle Perrot, Traverses, n°40, April 1987.

Marguerite Duras, “La maison” [The House], in: La vie matérielle, 1987.

✕

[Read more]

“Souvent les provisions étaient là, achetées du matin, alors il n’y avait plus qu’à éplucher les légumes, mettre la soupe à cuire et écrire.”

“Often the provisions were there, bought in the morning, so all that had to be done was to peel the vegetables, put the soup to cook and write.”

Marguerite Duras, “La maison” [“The House”], in: La vie matérielle, 1987.

1989

Carrie Mae Weems, “Untitled (Woman Feeding Bird)”, The Kitchen Table Series, 1989-90.

1995

Cynthia A. Brandimarte, “To Make the Whole World Homelike: Gender, Space, and America's Tea Room Movement”, Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 30, n°1, Spring 1995, p. 1-19.

1997

Audre Lorde, “Story Books on a Kitchen Table” [1976], in: Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company.

✕

[Read more]

“Out of her womb of pain my mother spat me

into her ill-fitting harness of despair

into her deceits

where anger re-conceived me

piercing my eyes like arrows

pointed by her nightmare

of who I was not

becoming.

Going away

she left in her place

iron maidens to protect me

and for my food

the wrinkled milk of legend

where I wandered through the lonely rooms of

afternoon

wrapped in nightmares

from the Orange and Red and Yellow

Purple and Blue and Green

Fairy Books

where White witches ruled

over the empty kitchen table

and never wept

or offered gold

nor any kind enchantment

for the vanished mother

of a black girl.”

Audre Lorde, “Story Books on a Kitchen Table” [1976], in: Audre Lorde, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company.

1999

La cuisine de Marguerite [Marguerite's Kitchen], Paris: Benoit Jacob, 1999. A collection of texts by Marguerite Duras accompanied by Marguerite Duras' recipes and transcriptions of radio interviews.

2000

bell hooks, All About Love : New Visions, New York: Harper & Row.

✕

[Read more]

“In The Knitting Sutra, Susan Lydon describes the labor of knitting as a freely chosen craft that enhances her awareness of the value of right livelihood, sharing: 'What I found in this tiny domestic world of knitting is endless; it runs broader and deeper than anyone might imagine. It is infinite and seemingly inexhaustible in its capacity to inspire, excite, and provoke creative insight.' Lydon sees the world that we have traditionally thought of as 'woman’s work” as a place to discover godliness through the act of creating domestic bliss. A blissful household is one where love can flourish.”

bell hooks, All About Love : New Visions, New York: Harper & Row.

2005

Myriame El Yamani, Médias et féminismes. Minoritaires sans paroles, Paris: L'Harmattan.

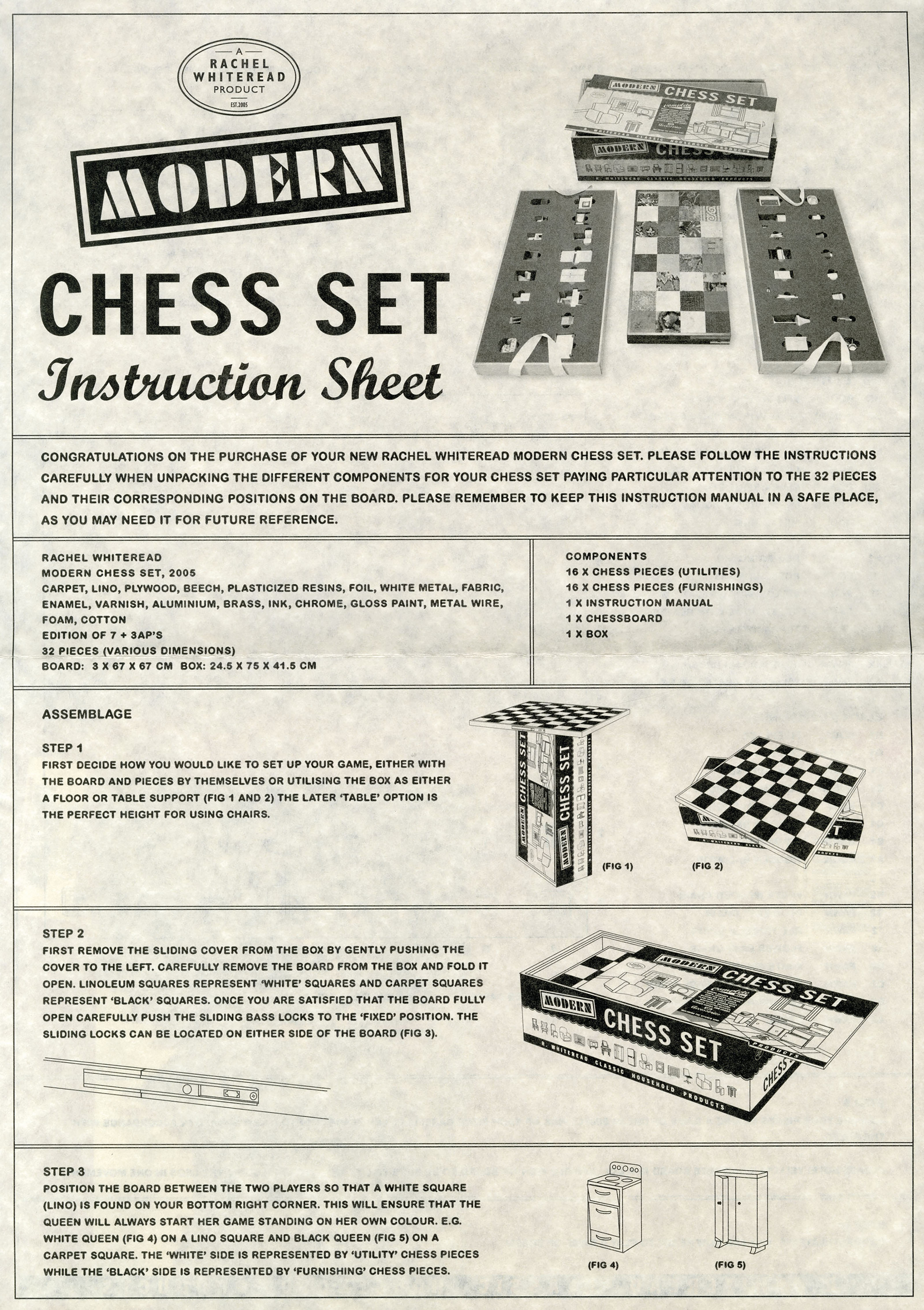

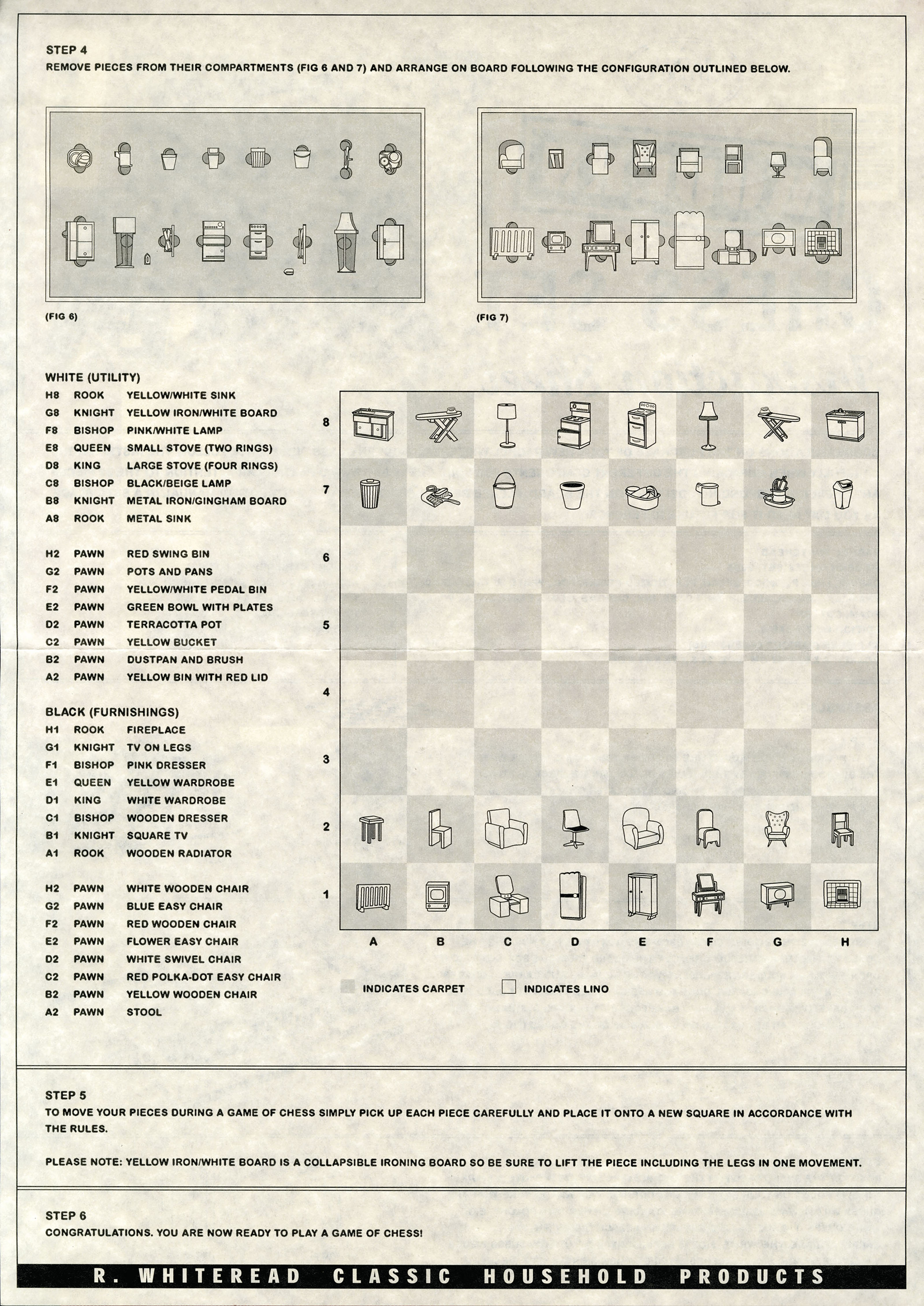

Rachel Whiteread, Modern Chess Set, 2005.

✕

[Read more]

Rachel Whiteread, Modern Chess Set, 2005.

2011

Sondra Hale, Terry Wolverton, From Site to Vision: The Woman's Building in Contemporary Culture, Los Angeles: Otis College of Art and Design.

2015

Mona Chollet, Chez soi. Une odyssée de l'espace domestique [Home. An Odyssey of Domestic Space], Paris: Zones.

Ana Bordenave, “Artistes femmes et arts visuels dans la revue Sorcières (1976 – 1982)”, master thesis in History of Arts, University Paris IV Sorbonne, under the supervision of Larisa Dryansky.

Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda, Remediating Mama Pina's Cookbook.

2016

Fashioning Yourself! A Story of Home Sewing, National Women's History Museum (online exhibit).

2017

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University Press.

✕

[Read more]

Sara Ahmed about the movie The Hours (dir. Stephen Daldry, 2002), where Laura is an unhappy housewife in the 1950s:

“What happens when domestic bliss does not create bliss? Laura tries to bake a cake. She cracks an egg. The cracking of the egg becomes a common gesture throughout the film, connecting the domestic labor of women over time. To bake a cake ought to be a happy activity, a labor of love. Instead, the film reveals a sense of oppression that lingers in the very act of breaking the eggs.

Not only do such objects not make you happy; they embody a feeling of disappointment. The bowl in which you crack the eggs waits for you. You can feel the pressure of its wait. The empty bowl feels like an accusation. Feminist archives are full of scenes of domesticity, in which domestic objects become strange, almost menacing. An empty bowl that feels like an accusation can be the beginning of a feminist life.”

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life, Durham: Duke University Press, p. 63.

Saul Pandelakis, “Note pour le design des cuisines déviantes” [“Note for the design of deviant kitchens”], lecture for the conference Espaces Genrés Sexués Queer, ENSA Paris La Villette and ENSA Belleville.

Judy Chicago on WomanHouse, National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2017.

2018

“A Short history of Bridge”, online story, National Women's History Museum.

2019

Christine Delphy, L'exploitation domestique, Paris: Syllepse.

2020

Gabrielle Stemmer, Clean with me (after Dark), La Fémis, 21 min, 2019.

Twitter account La vie Matérielle, described as “material culture/consumption, snack content, our tools, ourselves”, 2015–.